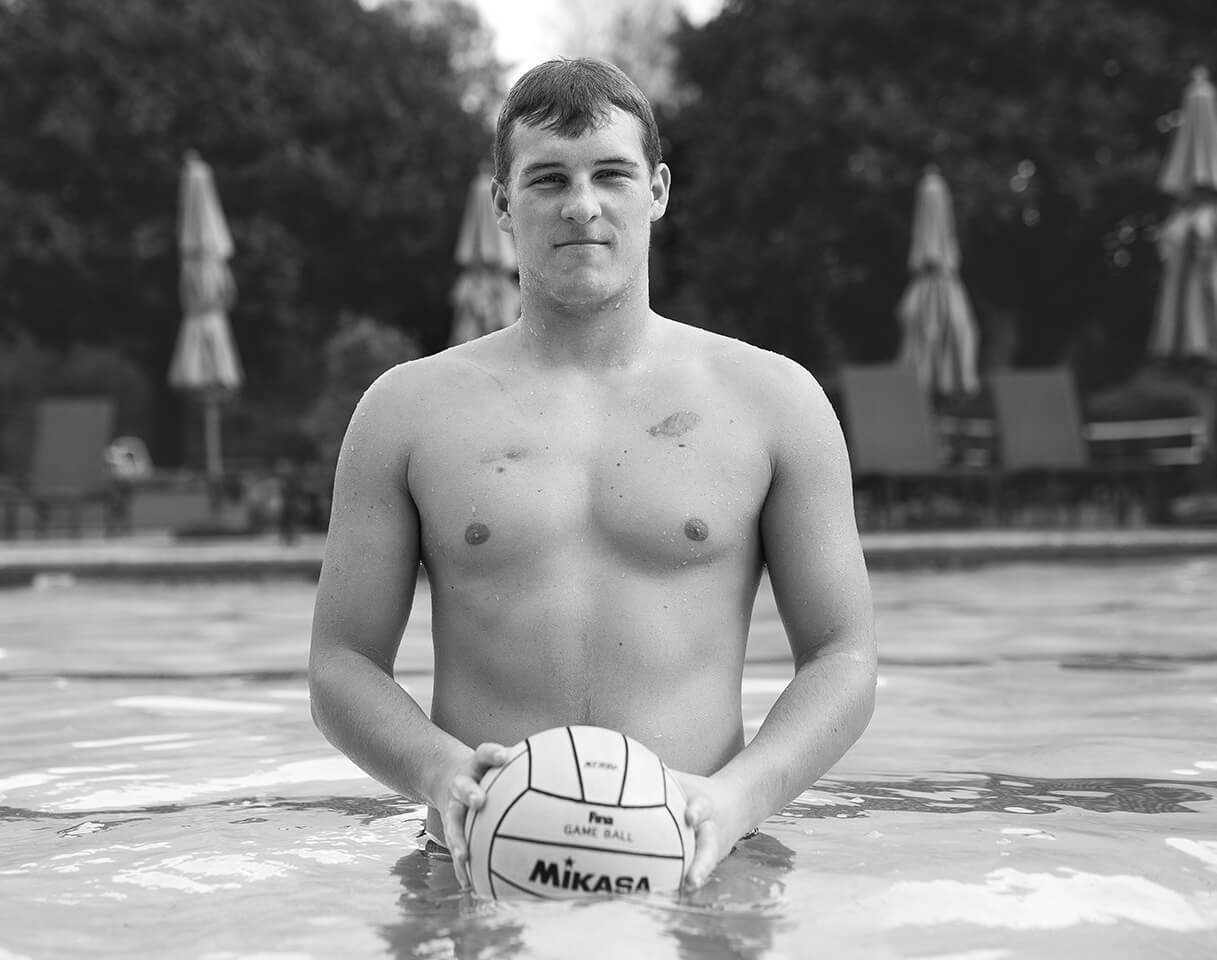

Miles approaches the pool and looks out over the iridescent surface, shimmering with light from above. He stretches his arms over his head and his body hints pure strength and power. His trapezius muscle rises up from his back and wraps around his widened neck like a muscular scarf. His deltoids bulge out from his shoulder blades like an overly-sleek pair of wings and his arms seem capable of lifting almost anything—but Miles doesn’t fly, he swims. His body pierces the still blue water, and in an instant he propels himself gracefully forward, from one side of the pool to the far end.

This is Miles’ home: in the water. Half-battleship, half-man, his life’s passion is water polo—a sport that has come to define this 18-year-old’s progress and aspirations as a young athlete. With a swift, determined move he grabs the floating yellow ball and in an explosion of spray and splash, and fires it into the net. A playful smile erupts onto his face. “I like water polo because it’s physical,” he says. “It’s a workout. It can be aggressive.” Miles plays center, a position that necessitates voracity, and he will be the first to illuminate his competitive streak. “There’s been a lot of fights and stuff,” he muses, describing some potent anecdotes from the game. “That’s fun, fighting with the other team.”

He regularly battles not just other high schoolers, but semi- and professional water polo players from all over the world as a member of the US Junior Olympic team. He also plays for his high school, club teams, and the US national squad. Two summers ago, Miles played on the US national team that almost clinched the world championship. “We came in second,” says Miles, holding a colorful medal proudly. “We lost to Brazil by one goal in the finals.” Reminiscing on his narrow defeats, Miles seems relatively unperturbed. “At the Junior Olympics we were in the third-place game and we had everyone out except for our starters. That meant we had no subs. We were tied at the end of regulation and the game went to a shootout. We ended up losing the shootout. It was real sad.” Some of his fondest memories of the game are comprised of close losses and he insists that these moments offer more opportunity than doubt. “It motivates me to train harder,” he says. And all his training is paying off. Miles stands poised to enter his freshman year of college at Princeton University, a result of many years of hard work. “My goal for water polo was to help me get into a good college,” he states. This will soon be reality. “I’m looking forward to going to school, meeting new people, and being independent.”

Watching Miles move—his speed, agility, and accuracy—it would be hard to imagine that anything is amiss. However, Miles is a severe hemophiliac, affected since birth by Hemophilia A. It is a disease that a generation ago would annul any possibility of Miles pursuing his passions, and it often relegated sufferers to a sedentary life. Despite that truth, Miles is on track to become the first athlete with severe Hemophilia to play Division I water polo—a trajectory that stands in direct contrast to the disease, and a testament to the merits of current treatments.

— Miles“My goal for water polo was to help me get into a good college. I’m looking forward to going to school, meeting new people, and being independent.”

“Without medicine, I wouldn’t be able to do anything,” admits Miles. “Even after two days, if I forget to infuse, I’ll wake up super achy and fragile.” It has become an almost daily routine for Miles to prophylactically inject himself with the clotting factor (factor VIII), that he was born without.

Only with the help from this factor is Miles able to do what he loves, solidifying his status as one of the game’s best junior competitors. “I’ve had to learn to work hard. If you work hard, you’re going to get better at the game.” Dedication and medication go hand-in-hand for Miles, whose unwavering focus on both water polo and his condition, is the true source of his undeniable success.

“We initially weren’t going to let him play such a rough sport,” says Susan, Miles’ mother. “We basically decided to just wait and see; if he gets injured we’ll stop. It turns out he was able to do it.” Along with her husband Joe, Miles’ parents have supported their son’s dreams and his ability to deny the limitations placed on him by Hemophilia. “I didn’t want him to buy into the idea that he’s different and there were things he couldn’t do,” recalls Susan. “I wanted him to see that there are so many things he can do.” Joe got involved with the Southern California Hemophilia Foundation, and eventually sat on the board as president. His knowledge of the condition helped keep the family informed, and helped break the assumptions of what the world saw as a hemophiliac. “We met a lot of families who were super cautious,” Joe says. “It was part of an older culture of Hemophilia. Most people I talked to knew someone back in high school, and most of them died, from AIDS. It’s a tough thing for the whole community. Miles has been pretty lucky.”

Access to factor is a crucial element of Miles’ success, and one that he and his family do not take for granted. “A large percentage of the world doesn’t have access to the medication,” says Susan, extolling on the tragic shortage of factor outside of the US. Furthermore, the family’s access to medical insurance has undoubtedly been a lifesaver. Each factor injection costs about $5,000, an insurmountable price for a family without health insurance. “I think we feel lucky about a lot of different things,” says Joe. “But having medical insurance is huge.” The prohibitive expense of the medication has changed the career outlook for Miles and other young hemophiliacs growing up in America. “With previous generations it was about finding a job you physically can do—like a desk job,” says Susan. “With the next generation it’ll be a matter of finding a job that can provide ample insurance. Miles’ life is going to be dictated by that.”

Despite Miles’ incredible physical vigor, his health will ultimately be determined by his access to medication. He is working hard now, utilizing his talents, to ensure his access to care in the future, all without fretting about it too much. “I’ll worry about it when I get there,” he says.

Aside from access to medication, another key element in Miles’ life is his ability to self-infuse. He first learned at the Painted Turtle, in Lake Hughes, CA, a summer camp focused on empowering children with life-threatening illnesses. Miles remembers feeling a little behind in his self-care abilities. “I was kind of a late-bloomer,” he says. “There were all these younger kids who already knew how.” But he challenged himself to learn, and at the age of eleven, did his first self-infusion at the camp. “They had a big ceremony,” recalls Miles. However, it would take another year for him to be comfortable regularly self-infusing. “It was a lot of learning, but after a while, it just clicked. I got used to it, and got better at it.” His self-care abilities came not a moment too soon—Miles was just starting to fall in love with water polo. It was also time for him to start to make his own life decisions “It was an interesting psychological thing,” adds Susan. “It was a sign of him becoming an adult… kind of like cutting the umbilical cord.”

This newfound freedom was a huge turning point for Miles who had spent much of his early life in the care of his parents and medical professionals. He was diagnosed after getting a postnatal shot that refused to stop bleeding. His parents were shocked. “I’d never heard of anyone with Hemophilia,” recalls Susan. Miles’ early months were laden with stress. “The first months were really hard… We were just in the hospital a lot.” Miles had an injection port surgically implanted into his chest at eight months old to help his parents with at-home care. Though as an adult he no longer uses his port, this was a huge step at the time, when bleeds were more common. “He was severe and he was active,” remembers Susan. “When he started crawling he got an elbow bleed. Once, he ate a piece of bacon and had a mouth bleed. Any little thing and he’d bleed.” As Miles grew, so did his parents’ understanding of his condition. Through education and involvement with the Hemophilia community in southern California, they found resources that would alleviate their stress and gave Miles the opportunity to achieve greatness. His parents’ tireless work has not gone unrecognized, despite the fact that Miles admits he doesn’t remember a lot of the tough times from his early childhood. “I haven’t had to go through much,” reflects Miles. “My parents really had to suffer and deal with it the most.”

Now, Miles is achieving bold independence, and looking towards his future. His parents hope that his diligence and focus on his condition continues to play an important role in his life. “We need to trust that he’ll be on it,” says Susan. “He’ll have to be his own advocate.” They want him to remain attentive and proactive, making sure he manages the risks associated with Hemophilia responsibly once he leaves home.

Ultimately, Miles doesn’t want to be defined by his condition and he sees the power of his story as inspiration for others to break free from expectations. “Hemophilia hasn’t held me back,” says Miles. “But it’s taught me compassion for people who have illnesses that hold them back.” He’s remained involved in the Hemophilia community, speaking at conferences, helping to host events at his parents’ house (such as an annual Hemophilia Foundation Christmas party), and has even tried to organize a water polo workshop for hemophiliacs. Miles continues to redefine living with Severe Hemophilia and challenges the notion that a disease should limit your life. “It would have been easier to have never began playing water polo—and then I wouldn’t be going to Princeton. I wouldn’t be in such good shape. I wouldn’t be having so much fun.”